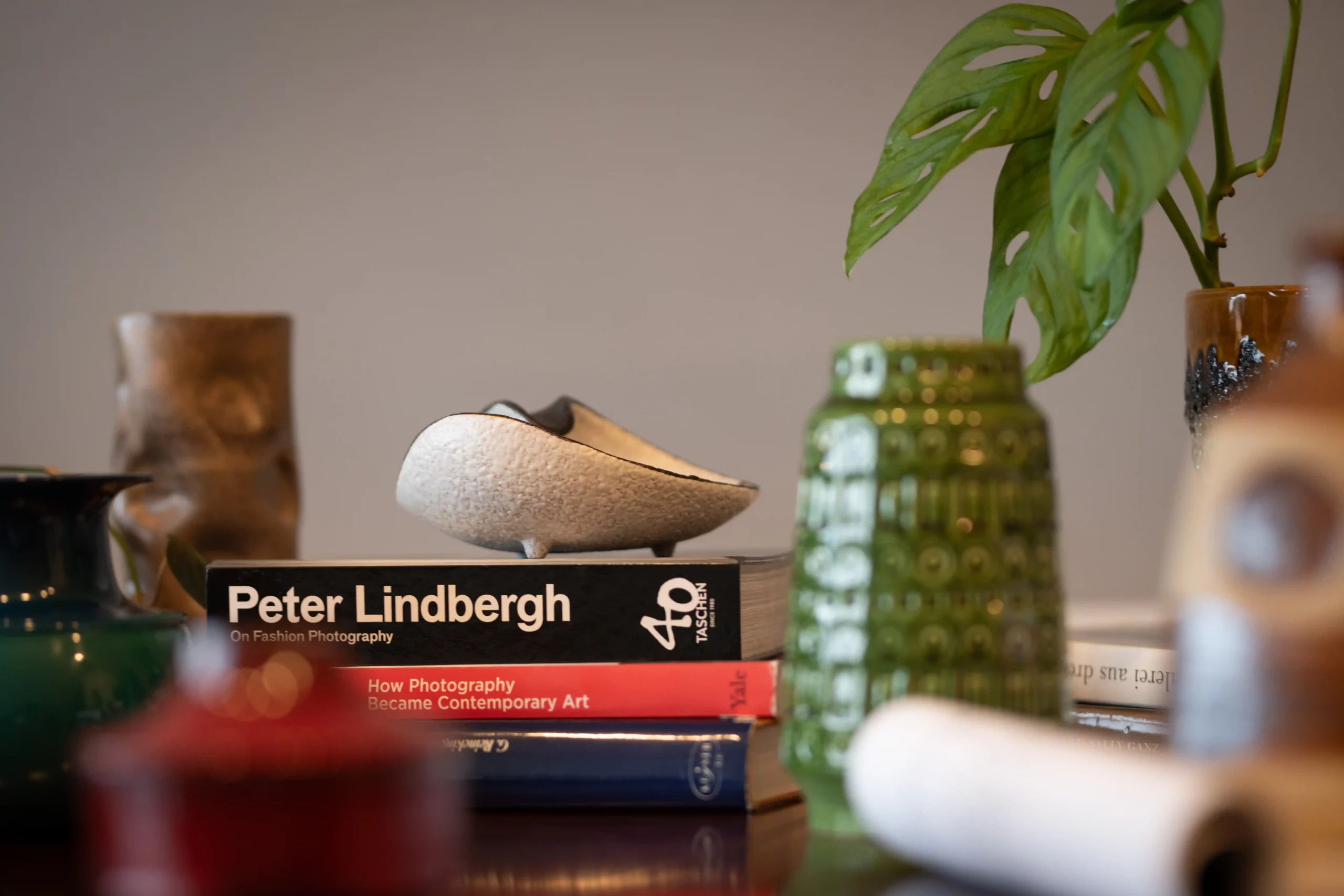

It is fascinating how cultural codes matter in the appreciation and evaluation of different art mediums. My big passion is studio pottery. As I live in Germany, I collect mainly local artists, as well as some from nearby countries — Denmark, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands.

Even though there is a market and interest in studio pottery in Germany, it is quite small and somewhat silent. It is interesting how Germans do not really appreciate their own art pottery. Let me give you an example: a studio pottery piece by the German ceramist Gerhard Liebenthron can sometimes be found on eBay Kleinanzeigen — the German equivalent of Facebook Marketplace or Craigslist — for between 30 and maybe 150 euros, depending on the condition of the piece and the seller. A similar piece on international platforms like 1stDibs or Pamono costs 400 euros or more.

The Japanese, Koreans, and Chinese are true ceramic and pottery lovers. In the introduction to Bernard Leach’s A Potter’s Book (1940), Soetsu Yanagi, director of the National Folk Museum in Tokyo at the time, wrote:

“Our people are born pottery lovers, for among us pottery making has for centuries been regarded as a true art, of equal dignity with the fine arts.”

When this is true regarding Yanagi’s people, it is not exactly true regarding the Germans, I guess. Somehow, deep down, I am a bit afraid that the art of studio pottery in Germany will stop being art and will become a decorative Handwerk — a German equivalent to handcraft.

Kunst versus Handwerk, art versus handcraft — this is quite a pickle. I sometimes wonder: does this question apply only to non–fine art mediums like ceramics, woodwork, or glass art? And whether there is handcraft in painting? I guess not — handcraft in painting is often called skill, and even more often, talent.